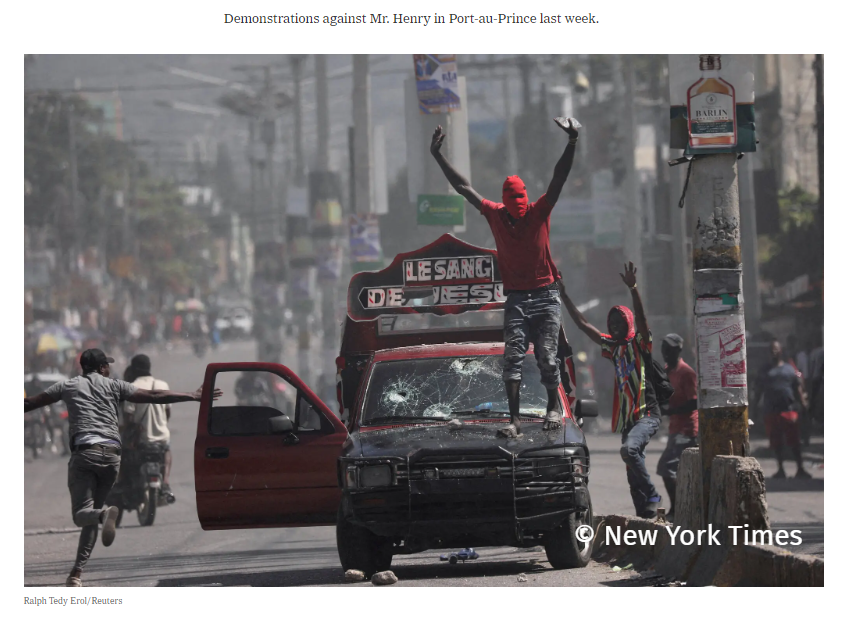

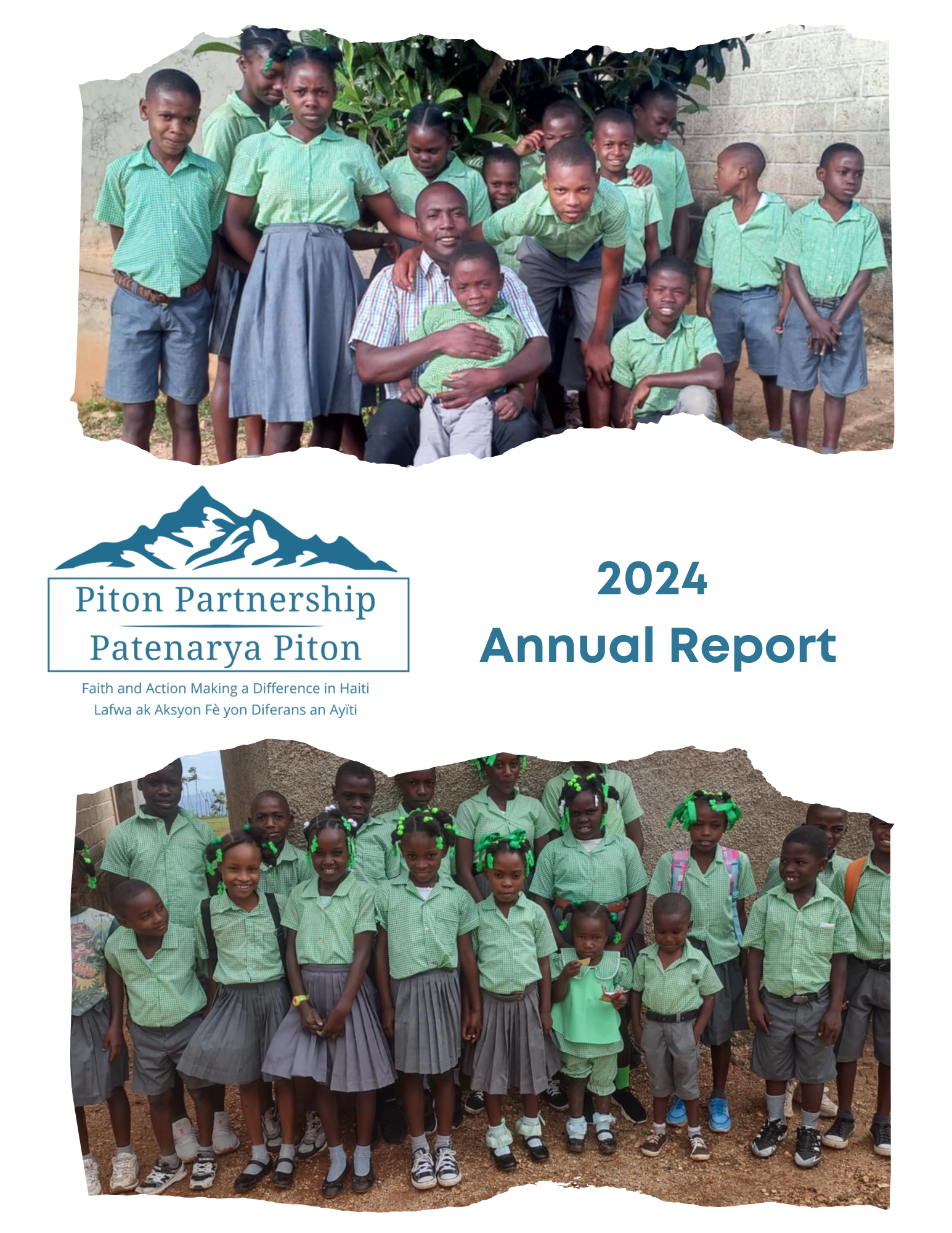

Air, hot and sticky and thick. A home made of crude concrete blocks, crumbly and rough. Windows made of uncovered holes in the wall, or of decorative brick that allow little air to flow through. Maybe there’s metal bars for security. The outside noise pushes in; sirens, dogs barking, voices yelling, the cockadoodledoo of a rooster who doesn’t care that the sun isn’t due to rise for hours. Then banging on the door. A gang? Scared neighbor warning us to leave? You grab your two children as your husband rushes you out the door. Leave it, leave everything. Outside in the swelter the sound of gunfire is jarring; rapid shots aimed who-knows-where. The added heat of fires burning tires or, worse, homes and buildings. You dash down the street looking for a tap tap (taxi) or a friend with a vehicle. Anything to get you out the neighborhood. You have family or a friend hours away in Petit Goave, on a mountain. Come here, they say, it’s safer. We have a school for your kids.

You travel through the night. Small flames shine through the gloom from people cooking on the street or selling goods. The solar powered street lights have been stolen. Your headlights and the headlights of oncoming traffic illuminate the legs of pedestrians and children. An occasional goat. Your ride slowly makes its way out of the sprawl of Port-au-Prince and the outlying communities into the rural night. Will you run into a roadblock? A gathering of bored gang members looking for trouble? As you travel the hours down Route 2, you hold your breath through smaller towns hoping they are quiet this night. Then a sharp left turn and suddenly the car is pointing upward at about a 40 degree angle. Less light here, less noise. Where are we going? Good lord is this the end of the land? How are we still going up? Not far now. You should be happy we have a road now to get all the way to the village rather than walking up the last quarter mile.